Immediately after Ted Kennedy’s unfortunate death, pundits and hopeful Democrats began positing that his death could actually serve as an emotional springboard for the final version of a healthcare bill that can pass. These remained whispers in the days immediately following the senator’s death. But now his colleague, and only living senator senior to Kennedy, Robert C. Byrd (WV) has offered to rename the bill in Kennedy’s honor.

The political result, pro-health care Americans hope, would be to further lionize the Lion of the Senate and his signature cause over his career—health care—and thus create a legislative momentum among lawmakers who knew and respected Kennedy.

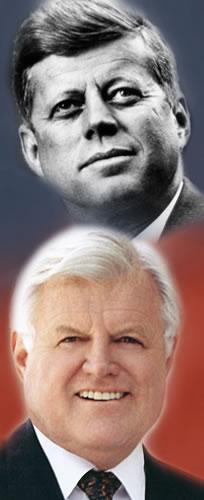

A similar strategy was undertaken in late 1963 immediately after his brother, President John F. Kennedy, was assassinated. JFK’s key domestic issue became the 1964 Civil Rights Act. Vice President Johnson picked up the ball and ran with it and invoked the popular president’s name and sacrifice in pressing for an anti-discrimination, public accommodations bill.

In his televised address, Johnson stated, “No memorial oration or eulogy could more eloquently honor President Kennedy’s memory, than the earliest passage of the civil rights bill for which he fought so long.” Days later on Thanksgiving, LBJ promoted the bill again, “for God made all of us, not some of us, in His image. All of us, not just some of us, are His children.” Lawmakers came together, except for those from the South, to pass the nation’s most expansive civil rights legislation ever.

In Senator Byrd’s memorial to Ted Kennedy, he said, “In his honor and as a tribute to his commitment…[lets] have a civilized debate on healthcare reform which I hope, when legislation has been signed into law, will bear his name for his commitment to insuring the health of every American.”

Will a similar pattern follow in Ted Kennedy’s name, because “the work goes on, the cause endures, the hope still lives, and the dream shall never die,” as he declared in his failed 1980 bid for the Democratic nomination. And he made a similar declaration at the end of his speech at the historical 2008 Democratic Convention when proclaimed, “The work begins anew, the hope rises again, and the dream lives on.”

Times are very similar to 1963-64. The nation is divided on some rather fundamental issues within the healthcare debate. The intensity of the dialogue was high then as it is now. Johnson and Obama have similar agendas in terms of social legislation. A question of moral responsibility and obligation loomed then as it does now.

But times are so very different. The Congress is not the same. In 1963, partisans spoke to one another in different terms. Congressional leaders saw eye-to-eye on the issue. There wasn’t the array of special interests, each with heavy influence and chips on the table.

Ted Kennedy, while the author of more far-reaching legislation than any elected official in recent history, is no Jack Kennedy.. The effect of a slain popular president carried more weight than the death of a loin in the Senate Plus unlike John Kennedy, Ted Kennedy’s personal moral failings, and representing the far left of his party has consistently maintained a vociferous stable of opponents.

So the looming question in the coming weeks: Will the timing of Ted Kennedy’s death and his life-long work on healthcare reform have a compelling effect on a very polarized Congress to pass a bill that will bring about real improvement in access to quality health care for the greatest number of Americans?